After the CISO Chair: How Cybersecurity Leaders Shape Their Next Executive Act

Why the skills you build as a CISO — not the title — determine whether your future is CIO, CTO, COO, or the private equity and venture capital table

For a long time, the CISO role was treated as the end of the line. You grind your way up through security engineering, incident response, compliance, and governance, and once you land the CISO title, that’s it — you’ve “made it.” That thinking is obsolete. Research from executive search firms, board advisory groups, and private equity operators over the last five years shows that the CISO role has quietly become one of the most versatile feeder roles in the enterprise.

What comes next, however, is not determined by the title itself but by the skills the CISO built while holding it. In other words, the CISO job is no longer a destination; it’s a sorting mechanism.

Take the CIO path. CISOs who move into CIO roles tend to be the ones who never treated security as a silo. They lived in ERP conversations, cloud migrations, identity platforms, data architecture, and uptime metrics. Their boards already trusted them with enterprise-wide tradeoffs, not just cyber risk. A clear example is Tim Callahan, who moved from the CISO role into the CIO seat at Aflac. That transition only works when the CISO has already been acting as a technology integrator, balancing cost, reliability, and speed rather than as a control enforcer.

If your CISO tenure was dominated by frameworks, audits, and tools with minimal ownership of delivery and operations, the CIO role is usually a bad fit, no matter how attractive the title sounds.

Then there’s the CTO path, which research shows is far less common but highly intentional. CISOs who become CTOs are builders. They understand engineering culture, software supply chains, cloud-native design, and the realities of shipping code at speed. These are the CISOs who pushed secure-by-design principles into development pipelines instead of bolting security on at the end.

Jamil Farshchi, after his time as CISO at Equifax, is a strong example of this trajectory — moving toward a role focused on technology strategy and execution rather than defensive posture alone. The hard truth here is simple: if you never cared how products were built, you won’t suddenly enjoy being responsible for building them.

One of the most underappreciated paths out of the CISO role is the COO route. Data from executive placement firms shows that CISOs with deep experience in crisis management, business continuity, third-party risk, and operational resilience increasingly show up on COO shortlists — especially in asset-heavy, regulated, or operationally complex businesses.

These CISOs weren’t just thinking about breaches; they were thinking about what happens when systems, suppliers, or regions fail. They learned how people, processes, and technology break under stress and how to put them back together fast. Boards like these CISOs because they’re calm in chaos and trained to make decisions with incomplete information — which, frankly, is most of operations.

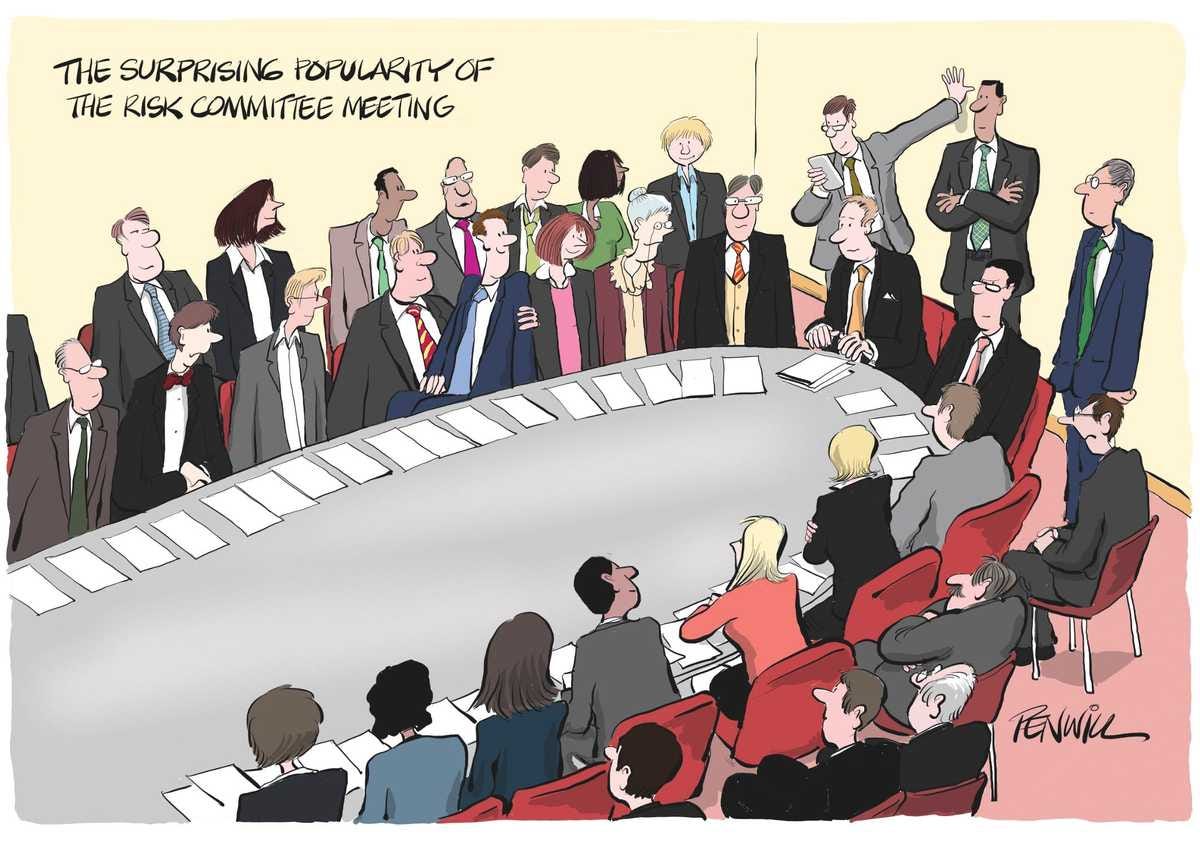

Another growing destination is risk leadership and board advisory roles. Some CISOs evolve into Chief Risk Officers or portfolio-level risk executives, particularly in financial services and highly regulated sectors. These leaders mastered the translation of cyber risk into financial exposure, regulatory impact, and enterprise value. They learned M&A due diligence, disclosure obligations, and how risk tolerance actually works at the board level — not how it’s described in policy documents. This path tends to attract CISOs who enjoy strategy, governance, and decision-making more than day-to-day operational ownership.

Where the data gets especially interesting is private equity and venture capital. Over the last few years, PE firms have increasingly pulled CISOs into operating partner, portfolio advisory, and diligence roles. These CISOs aren’t defending a single enterprise; they’re assessing dozens. Their value lies in pattern recognition identifying systemic security and operational risks across portfolios, accelerating remediation playbooks, and advising boards and management teams under tight timelines.

In VC, CISOs often act as trusted advisors to founders, helping early-stage companies avoid the architectural and governance mistakes that become existential problems later. This route strongly favors CISOs who understand business models, unit economics, and growth pressures, not just security controls.

The uncomfortable but necessary conclusion is this: your next role after CISO is already being decided by what you focus on while you’re in the chair. CISOs who obsess over enterprise architecture and delivery tend to become CIOs. Those who embed themselves in engineering become CTOs.

Those who live in resilience and crisis move toward COO roles. Those who translate risk into dollars end up in CRO, board, PE, or VC roles. Titles don’t open doors — skills do. And the CISOs with the most options are the ones who stopped thinking like security leaders only and started thinking like executives long before anyone offered them the next job.